Edmunds takes on the Environmental Protection Agency's electric vehicle performance estimates to achieve real-world results.

This item is available in full to subscribers.

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continue |

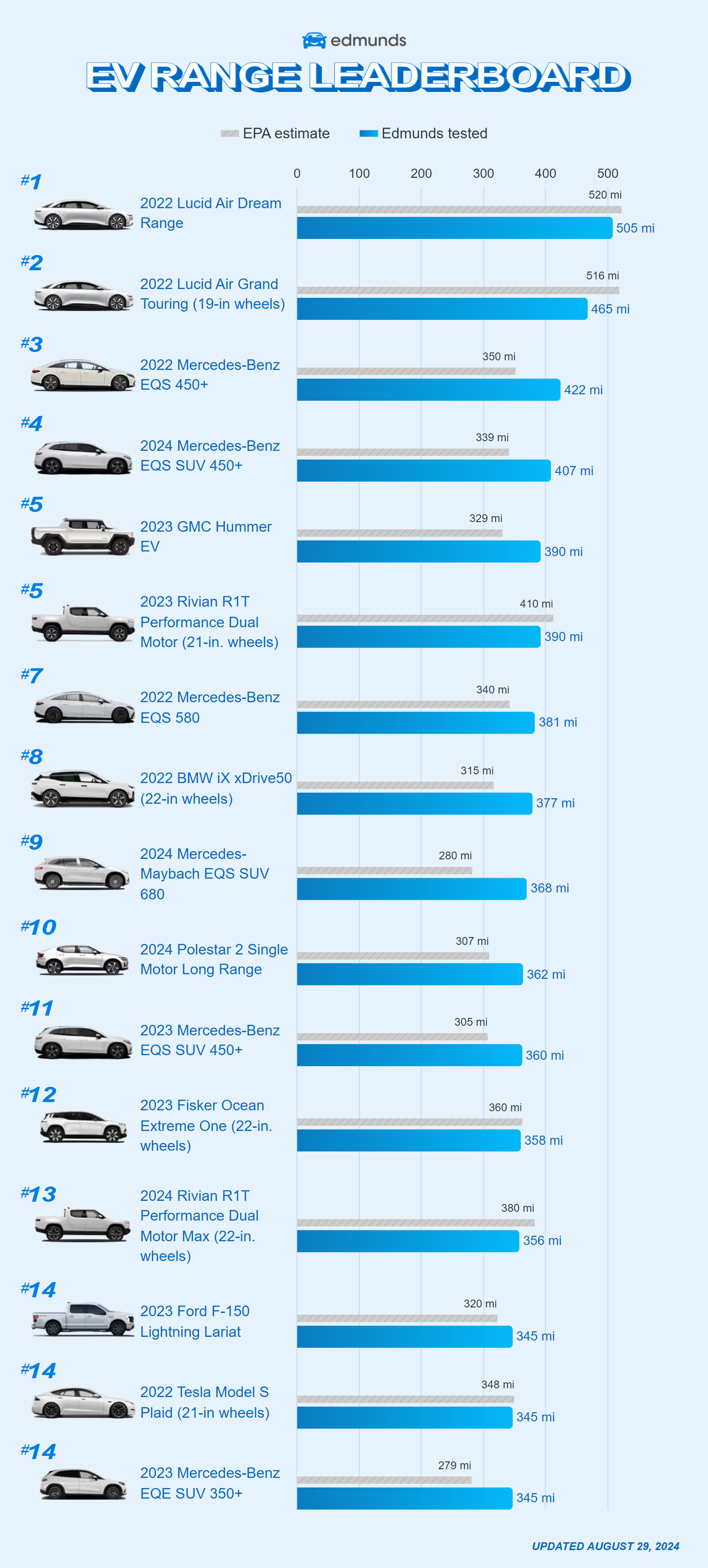

To see how realistic electric vehicle range estimates provided by the Environmental Protection Agency are, Edmunds tested all of them. Take a look at the leaderboard to see the results.

The results of the Edmunds EV Range and Efficiency Test vs. range estimates from the EPA were updated at the end of August 2024.

This chart shows an electric vehicle's official EPA range and energy consumption compared to the range and consumption results from Edmunds' own testing, which is designed to be a real-world complement to the EPA's laboratory-based process.

In short, this is the approximate number of miles that a vehicle can travel in combined city and highway driving (using a mix of 55% highway and 45% city driving) before needing to be recharged, according to the EPA's testing methodology.

But what exactly is that methodology? First, the vehicle is fully charged and parked overnight. The following day, the vehicle is driven on a dynamometer—it's like a treadmill for cars—over successive simulated city and highway routes until the battery is depleted. The total distance traveled is then multiplied by a correction factor that the EPA has determined will more accurately reflect what drivers can expect to achieve in the real world. The value of this correction factor, which is always less than one but greater than zero, is determined by the number of drive cycles a vehicle is tested on.

In short, there's certainly a method to the EPA's madness, but the process is laboratory-based, and EV owners don't drive their cars in a lab. So what's the real-world version? That's where Edmunds' EV range testing comes in.

Akin to miles per gallon (mpg) for fuel-burning vehicles, this metric represents electric vehicles' energy consumption in kilowatt-hours per hundred miles (kWh/100 miles). A battery stores energy in kilowatt-hours much like a gas tank stores fuel in gallons. This value tells you how much energy in kilowatt-hours a vehicle would use to travel 100 miles.

Unlike mpg, however, where a larger number is better (for example, a vehicle that gets 30 mpg is better than one that gets 20 mpg), a smaller number is better in kWh/100 miles because you are using less battery energy per mile. So a vehicle that uses 20 kWh/100 miles is more efficient than one that uses 30 kWh/100 miles.

In EPA testing, once a vehicle battery is depleted, it is recharged using the manufacturer-supplied charger for that vehicle. The energy consumption is then determined mathematically from the recharging energy, the energy-discharge data from the vehicle, and the distance traveled for each cycle. The recharge energy includes any charging losses due to inefficiencies in the manufacturer's charger.

Edmunds begins with full battery charge and drives an electric vehicle on a mix of city and highway roads (approximately 60% city, 40% highway) until the battery is almost entirely empty. (We target 10 miles of remaining range for safety.) The miles traveled and the indicated remaining range are added together for the Edmunds total tested range figure. We prefer to use a higher percentage of city road driving because we believe it's more representative of typical EV use.

After a vehicle completes its road loop and the battery is nearly empty, it's charged back to full capacity. The kilowatt-hours used from plug-in to a full charge are tracked and then we calculate the consumption based on the miles traveled (less the remaining range). This process takes into account charging losses in the Edmunds tested consumption number.

This figure is the difference between the EPA's range estimate and the range tested in Edmunds' real-world testing. A positive percentage (in green) means Edmunds exceeded the range estimated by the EPA, while a negative percentage (in red) means a vehicle fell short of its EPA range during Edmunds' test.

This figure is the difference between the EPA's energy consumption estimate and the energy consumption Edmunds calculated based on real-world testing. A positive percentage (in green) means a vehicle used that much less energy than its EPA estimate and was more efficient in Edmunds' testing. A negative percentage (in red) means a vehicle used that much more energy than its EPA estimate and was less efficient in Edmunds' testing. Remember, a lower kWh/100 miles number is better if you're talking EVs.

Ambient temperature—how cold or hot it is outside—matters a whole lot when it comes to electric vehicle range, so Edmunds lists the daily average temperature on the day of testing. California, and more specifically Los Angeles, has one of the more temperate climates in the world, which helps keep testing conditions relatively consistent throughout the year. But since the weather can't be controlled, it can at least be reported.

The roads

Edmunds drives on specific road routes that cover both highway and city driving around the greater Los Angeles area, aiming for a mix of 60% city driving and 40% highway driving, assuming that most electric vehicle owners will likely spend more time in stop-and-go traffic than they will on the open highway. Since no electric vehicle has exactly the same range, the route length is adapted to suit each vehicle.

The methodology

In EPA tests, a vehicle is run in the default settings at startup. If there are more efficient drive modes available, or if you can increase the level of regenerative braking, but the vehicle doesn't default to these settings, they won't be utilized. Edmunds' standard practice is to use the most efficient drive mode as long as it doesn't affect safety or practical comfort levels, such as deactivating the climate control system or significantly reducing power for accelerating or maintaining appropriate highway speeds.

Edmunds runs with windows up and the climate control set to auto at 72 degrees, and maximizes regenerative braking during stops. Posted speed limits are followed and kept within 5 mph of them, traffic and conditions permitting.

The short answer is neither. So many factors contribute to how far an electric vehicle will travel on a single charge that to come up with a single figure for every situation is impossible. The EPA's testing is highly controlled and standardized, but as Edmunds' testing has found, the real-world correlation can vary dramatically depending on the vehicle.

Because Edmunds' testing uses a more conservative driving style and puts greater emphasis on city driving over highway driving (compared to the EPA's mix), figures will often be on the higher end for range, which usually equates to better efficiency. But that's not always the case. Overall, Edmunds' figures are intended to provide EV owners and potential customers with an additional data point so that they can make more informed decisions.

Note: To date, every Tesla vehicle we've run on our real-world test route has failed to hit its EPA range estimate within the testing parameters described above, whereas most non-Tesla vehicles have surpassed their EPA estimates. Please refer to the chart above for our full test results.

This story was produced by Edmunds and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.